“In an age when more and more artists are using the computer to manipolate their imagery, Anna Esposito creates her works purely by means of manual dexterity and the most elementary of tools – scissors and glue. Her skill is the ability to invent new relashionship between unrested imagery. And at a time when religious themes in art are increasingly controversial and potentially explosive, Esposito treats religion as a jokey, almost surreal, exprerience.

In the gospel accroding to Esposito, Saint Sebastian (1992) is a truckload of eletric saws pinned to the forked trunk of a tree, the whole composition resembling the familiar, iconographic male torso pierced by arrows. Noah’s Ark (1998) is a rusty ship, a scene based on a picture of a boat- load of Albanese refugees arriving at the italian coast. The heads of various wild beasts poke out from the human mass; a pair of pandas cling to the rails, there are a couple of giraffes on the top deck, an antelope peers over the stern, an orangutan swings from the anchor. In Esposito’s hands, Buddha (1997) is in fact antropomorphic car-seat sitting on a lotus pad, a serene form of spirituality and industrial design. The decor is Eastern, the upholstery is synthetic, the mood is calmly ridicolous. She ‘dresses’ a pair of columns in St Peter’s Square in bright red underpants lebelled with the fortuitos brandname, Eminence. Meanwhile, Benediction (1994) shows Pope John Paul II performing a religious rite, the spiritual smoke becoming a billowing cloud of vulcanic ash behind him. The Gods, it seems, are angry.

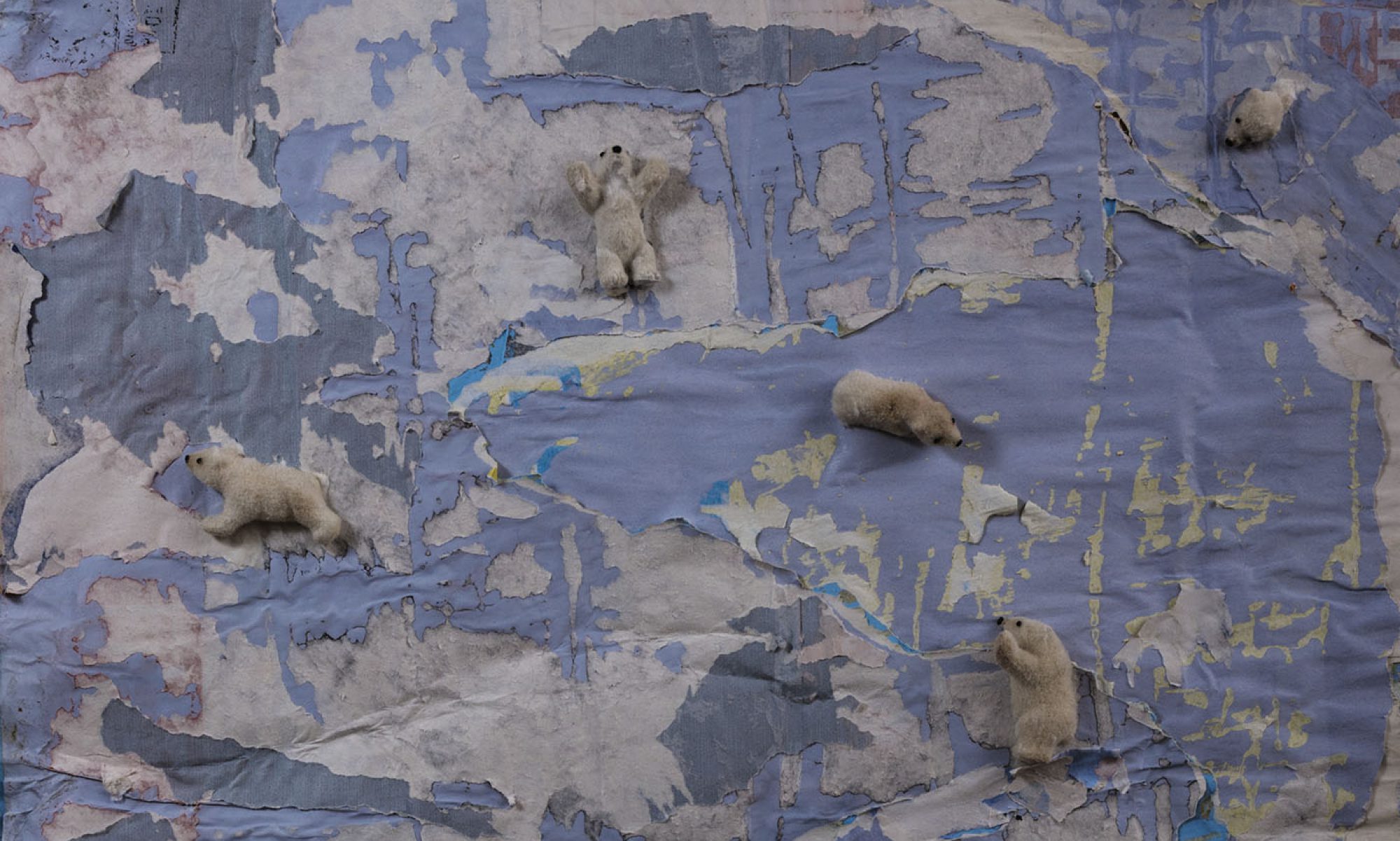

The biblical fable of feeding the multitudes is reinterpreted by the artist in Tortellini (1998). An outsized plate-load of pasta splills into an assembly of Japanese schoolgirls. The shapes of their straw hats are mixed up with the round forms of the tortellini. Many of Esposito’s recent works are about creating disorder from images of repetition. The last guards in a pa- rade of English Beefeaters topple like dominos. In another collage, the berets worn by a troop of marching soldiers are actually white Drawing – pins stuck into the paper. In Anna Esposito’s world, the viewer’s eye is lulled into a false sense of security by the idea of repetition. It is only upon closer inspection that we realise that something is truly amiss. Nature is upset and logic is over-ruled. So, of course, the Gods are angry.

[Jonathan Turner, Sydney, December 1998]